Bureau of Advertising | Diesen Artikel weiterempfehlen! |

Rede "The President and the Press", Bureau of Advertising, American Newspaper Publishers Association

Rede "The President and the Press", Bureau of Advertising, American Newspaper Publishers Association(New York, 27. April 1961)

Herr Vorsitzender, sehr geehrte Damen und Herren:

Ich bedanke mich sehr führ ihre großzügige Einladung, heute Abend bei ihnen sein zu dürfen.

Sie tragen eine schwere Verantwortung in diesen Tagen und einen Artikel, den ich vor einiger Zeit las, erinnerte mich daran, wie besonders stark sich diese Belastungen der aktuellen Ereignisse auf Ihren Beruf auswirken.

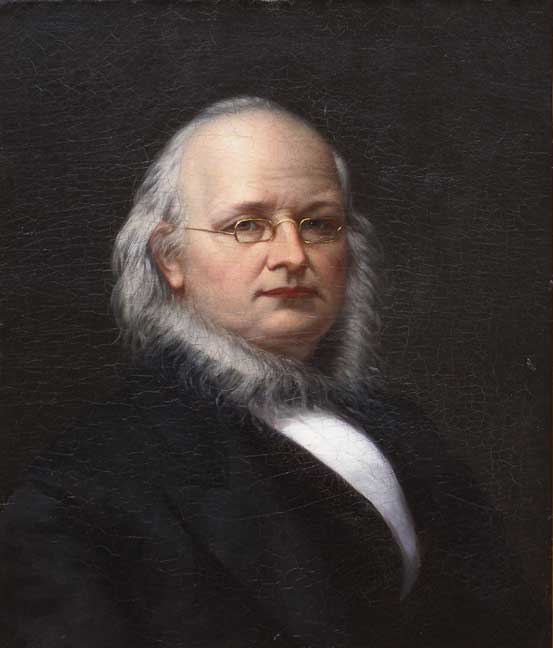

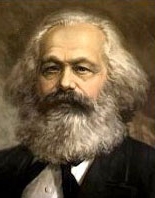

Vielleicht erinnern Sie sich, dass im Jahr 1851 die New York Herald Tribune unter der Schirmherrschaft und verlegen von Horace Greeley, als London-Korrespondent einen einfachen Journalist mit dem Namen Karl Marx beschäftigte.

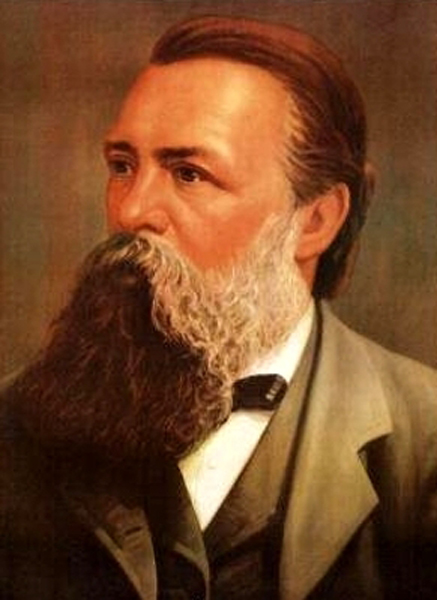

Uns wird gesagt, dass der Auslandskorrespondenten Marx, verarmt und mit einer kranken und unterernährten Familie, ständig Greeley und Chefredakteur Charles Dana um eine Erhöhung seines Selbstständigen-Gehaltes von 5$ pro Beitrag bat - ein Gehalt, dass er und Engels als undankbar und "lausigen kleinbürgerlichen Betrug" bezeichneten. Aber als alle seine finanziellen Forderungen abgelehnt wurden, sah sich Marx nach anderen Wegen zur Sicherung seines Lebensunterhaltes und zur Ruhmeserlangung um und beendet schließlich seine Beziehung zur Tribune und widmet seine Talente ganz der Sache, der Welt die Saat des Leninismus, Stalinismus, der Revolution und des Kalten Krieges zu vererben.

Wenn ihn nur diese kapitalistische New Yorker Zeitung besser behandelt hätte, wenn Marx nur ein Auslandskorrespondent geblieben wäre, könnte Geschichte anders verlaufen sein. Und ich hoffe, dass alle Verlage diese Lektion beherzigen, falls sie in nächster Zeit eine Bitte um eine geringe Erhöhung des Gehaltes von einem einfachen Zeitungsmann erhalten.

Ich habe als Titel meiner heutigen Ausführungen gewählt: "Der Präsident und die Presse". Einige könnte anmerken, es sei besser formuliert zu sagen: "Der Präsident gegen die Presse". Aber das entspräche nicht meinen Gefühlen heute Abend. Es ist jedoch wahr, dass, als ein bekannter Diplomat eines anderen Landes vor kurzem forderte, dass unsere Auswärtiges Amt bestimmte Zeitungs-Angriffe auf seine Kollegen zurückwies, uns eine Antwort unnötig erschien, da diese Behörde nicht zuständig für die Presse ist, und die Presse bereits deutlich gemacht hatte, dass sie nicht dieser Behörde untersteht.

Dennoch ist meine Absicht hier heute Abend nicht der übliche Angriff auf die sogenannte Ein-Parteien-Presse. Im Gegenteil - in den letzten Monaten habe ich - mit Ausnahme von ein paar Republikanern - selten von Beschwerden über politische Voreingenommenheit in der Presse gehört. Auch ist es nicht meine Absicht, heute Abend die Fernsehübertragungen der präsidentialen Pressekonferenzen zu diskutieren oder zu verteidigen. Ich denke, es ist sehr nützlich für 20 Mio. Amerikaner regelmäßig bei diesen Konferenzen, wenn ich so sagen darf, die prägnante, intelligente und höfliche Qualitäten Ihrer Washington-Korrespondenten zu beobachten. Noch sind schließlich diese Bemerkungen bestimmt, das richtige Maß an Privatsphäre, welches die Presse einem Präsidenten und seiner Familie ermöglichen sollte, zu untersuchen.

Wenn in den letzten Monaten Ihre Weißes-Haus-Reporter und Fotografen regelmäßig am Gottesdienst teilgenommen haben, hat es ihnen mit Sicherheit nicht geschadet. Auf der anderen Seite merke ich, dass Ihre Mitarbeiter und unabhängige Fotografen beklagen, dass sie nicht in den Genuss die gleichen grünen Privilegien auf den Golfplätzen kommen, wie sie es einst taten. Es ist wahr, dass mein Vorgänger nicht wie ich den Bildern der eigenen Golf-Fähigkeiten in Aktion widersprach. Aber auf der anderen Seite hatt er immer einen Secret Service Mann neben sich.

Mein Thema heute ist ein nüchternes Anliegen an Verlage wie an Herausgeber.

Ich möchte über unsere gemeinsame Verantwortung im Angesicht einer Gefahr reden, die uns alle betrifft. Die Ereignisse der letzten Wochen haben vielleicht geholfen, diese Herausforderung für einige zu erhellen (to illuminate); aber die Dimensionen der Bedrohung waren seit Jahren am Horizont zu erkennen. Was auch immer unsere Hoffnungen für die Zukunft sind - diese Bedrohung zu reduzieren oder mit ihr zu leben -, es gibt kein Entkommen von ihr, weder von der Schwere noch der Totalität ihrer Herausforderung für unser Überleben und unserer Sicherheit - es ist eine Herausforderung, die uns auf außergewöhnliche Weise in jeglicher Sphäre menschlicher Aktivitäten konfrontiert.

Diese tödliche Herausforderung stellt an unsere Gesellschaft zwei Anforderungen, die den Präsidenten und die Presse direkt betreffen - zwei Ansprüche, die fast widersprüchlich zu sein scheinen, die aber im Einklang gebracht und denen wir gerecht werden müssen, damit wir diese nationalen und großen Gefahr begegnen können. Ich spreche zuerst über die Notwendigkeit weit grösserer öffentlicher Informationen; und zweitens über die Notwendigkeit weit größerer amtlicher Geheimhaltung.

Allein das Wort Geheimhaltung ist in der freien und offenen Gesellschaft unannehmbar; und als Volk sind wir von Natur aus und historisch Gegner von Geheimgesellschaften, geheimen Eiden und geheimen Beratungen.

Wir entschieden schon vor langer Zeit, dass die Gefahren exzessiver, ungerechtfertigter Geheimhaltung sachdienlicher Fakten die Gefahren bei Weitem überwiegen, mit denen die Geheimhaltung gerechtfertigt wird. Selbst heute hat es wenig Wert, den Gefahren, die von einer abgeschotteten Gesellschaft ausgehen, zu begegnen, in dem man die gleichen willkürlichen Beschränkungen nachahmt.

Selbst heute hat es kaum Wert, das Überleben unserer Nation sicherzustellen, wenn unsere Traditionen, nicht mit ihr überleben. Und es gibt die schwerwiegende Gefahr, dass ein verkündetes Bedürfnis nach erhöhter Sicherheit von den Ängstlichen dazu benutzt wird, seine Bedeutung auf die Grenzen amtlicher Zensur und GEheimhaltung auszuweiten.

Ich beabsichtige nicht, dies zu erlauben, soweit es in meiner Macht steht, und kein Beamter meiner REgierung, ob sein Rang hoch oder niedrig sei, zivil oder militärisch, sollte meine Worte von heute Abend als Entschuldigung dafür interpretieren, die Nachrichten zu zensieren, Widerspruch zu unterdrücken, unsere Fehler zu vertuschen, oder von der Presse oder der Öffentlichkeit Fakten fern zu halten, die sie zu wissen begehren. Aber ich bitte jeden Herausgeber, jeden Chefredakteur und jeden Nachrichtenmann der Nation, seine Geflogenheiten erneut zu untersuchen und die Natur der großen Bedrohung für unsere Nation wahrzunehmen.

In Zeiten des Krieges teilen Regierung und Presse für gewöhnlich das Bemühen, hauptsächlich auf Selbstdisziplin beruhend, nicht autorisierte Enthüllungen an den Feind zu vermeiden. In Zeiten von "deutlicher und präsenter Gefahr" haben selbst die Gerichte entschieden, das sich sogar die privilegierte Rechte der ersten Verfassungssatzes der nationalen Notwendigkeit öffentlicher Sicherheit unterordnen müssen. Heute ist jedoch kein Krieg erklärt worden - und wie heftig der Kampf auch sein mag, vielleicht wird er nie in traditioneller Weise erklärt werden. Unsere Lebensweise wird angegriffen. Jene, die sich selbst zu unserem Feind gemacht haben, schreiten rund um den Globus voran. Dabei ist bisher kein Krieg erklärt worden, keine Grenze wurde von Truppen überschritten, kein Schuss ist gefallen.

Wenn die Presse auf eine Kriegserklärung wartet, bevor sie die Selbstdisziplin unter Kampfbedingungen annimmt, so kann ich nur sagen, dass kein Krieg jemals eine größere Gefahr für unsere Sicherheit darstelle. Wenn Sie auf einen Beweis "deutlicher und präsenter Gefahr" warten, dann kann ich nur sagen, dass die Gefahr niemals deutlicher und ihre Präsenz niemals spürbarer war.

Es bedarf einer Änderung der Perspektive, einer Änderung der Taktik, einer Änderung der Mission - seitens der Regierung, seitens der Menschen, von jedem Geschäftsmann oder Gewerkschaftsführer und von jeder Zeitung.

Denn wir stehen rund um die Welt einer monolithischen und ruchlosen Verschwörung gegenüber, die sich vor allem auf verdeckte Mittel stützt, um ihre Einflusssphäre auszudehnen - auf Infiltration anstatt Invasion; auf Unterwanderung anstatt Wahlen; auf Einschüchterungen anstatt freier Wahl; auf nächtliche Guerillaangriffe anstatt auf Armeen bei Tag.

Es ist ein System, das mit gewaltigen menschlichen und materiellen Resourcen eine eng verbundene, komplexe und effiziente Maschinerie aufgebaut hat, die militärische, diplomatische geheimdienstliche, wirtschaftliche, wissenschaftliche und politische Operationen kombiniert. Ihre Pläne werden nicht veröffentlicht, sondern verborgen, ihre Fehlschläge werden begragen, nicht publiziert, Andersdenkende werden nicht gelobt, sondern zum Schweigen gebracht, keine Ausgabe wird infrage gestellt, kein Gerücht wird gedruckt, kein Geheimnis wird enthüllt. Sie dirigiert den "Kalten Krieg" mit einer, kurz gesagt, Kriegsdisziplin, die keine Demokratie jemals aufzubringen erhoffen oder wünschen könnte.

Kein Präsident sollte eine öffentliche Prüfung seines Progamms fürchten. Denn aus so einer Prüfung kommt Verstehen und vom Verstehen kommt Unterstützung der Opposition und beides ist notwendig. Ich bitte Ihre Zeitungen nicht, die Regierung zu unterstützen, aber ich bitte Sie um Ihre Mithilfe bei der enormen Aufgabe, das amerikanische Volk zu informieren und zu alarmieren, weil ich vollstes Vertrauen in die Reaktion und das Engagement unserer Bürger habe, wenn sie über alles uneingeschränkt informiert werden. Ich will die Kontroversen unter Ihren Lesern nur nicht ersticken, ich begrüsse sie sogar. Meine Regierung will auch ehrlich zu ihren Fehlern stehen, weil ein kluger Mann einst sagte: "Irrtümer werden erst zu Fehlern, wenn man sich weigert, sie zu korrigieren".

Wir haben die Absicht, volle Verantwortung für unsere Fehler zu übernehmen und wir erwarten von Ihnen, dass Sie uns darauf hinweisen, wenn wir das versäumen. Ohne Debatte, ohne Kritik kann keine Regierung und kein Land erfolgreich sein, und keine Republik kann überleben. Deshalb verfügte der athenische Gesetzgeber Solon, dass es ein Verbrechen für jeden Bürger sei, vor Meinungsverschiedenheiten zurückzuweichen, und genau deshalb wurde unsere Presse durch den ersten Verfassungszusatz geschützt. Die Presse ist nicht deshalb das einzige Geschäft, das durch die Verfassung spezifisch geschützt wird, um zu amüsieren und Leser zu gewinnen, nicht um das Triviale und Sentimale zu fördern, nicht um das Publikum immer das zu geben, was es gerade will, sondern um über Gefahren und Möglichkeiten zu informieren, um aufzurütten und zu reflektieren, um unsere Krisen festzustellen und unsere Möglichkeiten aufzuzeigen, um zu führen, zu formen, zu bilden, und manchmal sogar die öffentliche Meinung herauszufordern. Das bedeutet mehr Berichte und Analysen von internationalen Ereignissen, denn das alles ist heute nicht mehr weit weg, sondern ganz in der Nähe und zu Hause. Das bedeutet mehr Aufmerksamkeit für besseres Verständnis der Nachrichten sowie verbesserte Berichterstattung, und es bedeutet schließlich, dass die Regierung auf allen Ebenen ihre Verpflichtung erfüllen muss. Sie mit der bestmöglichen Information zu versorgen und dabei die Beschränkungen durch die nationale Sicherheit möglichst gering zu halten.

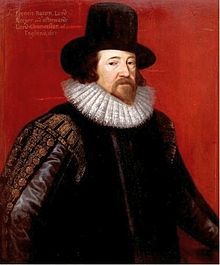

Es war bereits im frühen siebzehnten Jahrhundert, als Francis Bacon mit drei neuerlichen Erfindungen die Welt veränderte: der Kompass, das Schießpulver und die Druckerpresse. Jetzt haben uns die Verbindungen zwischen den Völkern, vom Kompass geschmiedet, gemeinsam zu Bürgern der Welt gemacht, und die Hoffnungen und Gefahren für einen immer zu den Hoffnungen und Gefahren von uns allen. In diesem weltweiten Bemühen, zusammen zu leben, hat uns die Entwicklung des Schießpulvers die ultimativen Grenzen der Menschheit und die schrecklichen Folgen ihres Scheiterns aufgezeigt.

So ist es die Presse, die Protokollführerin der Taten der Menschen, die Bewahrerin seines Gewissens, die Botin seiner Nachrichten, in der wir Stärke und Beistand suchen, zuversichtlich, dass mit Ihrer Hilfe der Mensch das sein wird, wozu er geboren wurde: frei und unabhängig.

Originalversion:

Originalversion:Mr. Chairman, ladies and gentlemen:

I appreciate very much your generous invitation to be here tonight.

You bear heavy responsibilities these days and an article I read some time ago reminded me of how particularly heavily the burdens of present day events bear upon your profession.

You may remember that in 1851 the New York Herald Tribune under the sponsorship and publishing of Horace Greeley, employed as its London correspondent an obscure journalist by the name of Karl Marx.

We are told that foreign correspondent Marx, stone broke, and with a family ill and undernourished, constantly appealed to Greeley and managing editor Charles Dana for an increase in his munificent salary of $5 per installment, a salary which he and Engels ungratefully labeled as the "lousiest petty bourgeois cheating."

But when all his financial appeals were refused, Marx looked around for other means of livelihood and fame, eventually terminating his relationship with the Tribune and devoting his talents full time to the cause that would bequeath the world the seeds of Leninism, Stalinism, revolution and the cold war.

If only this capitalistic New York newspaper had treated him more kindly; if only Marx had remained a foreign correspondent, history might have been different. And I hope all publishers will bear this lesson in mind the next time they receive a poverty-stricken appeal for a small increase in the expense account from an obscure newspaper man.

I have selected as the title of my remarks tonight "The President and the Press". Some may suggest that this would be more naturally worded "The President versus the Press". But those are not my sentiments tonight.

It is true, however, that when a well-known diplomat from another country demanded recently that our State Department repudiate certain newspaper attacks on his colleague it was unnecessary for us to reply that this Administration was not responsible for the press, for the press had already made it clear that it was not responsible for this Administration.

Nevertheless, my purpose here tonight is not to deliver the usual assault on the so-called one party press. On the contrary, in recent months I have rarely heard any complaints about political bias in the press except from a few Republicans. Nor is it my purpose tonight to discuss or defend the televising of Presidential press conferences. I think it is highly beneficial to have some 20,000,000 Americans regularly sit in on these conferences to observe, if I may say so, the incisive, the intelligent and the courteous qualities displayed by your Washington correspondents.

Nor, finally, are these remarks intended to examine the proper degree of privacy which the press should allow to any President and his family.

If in the last few months your White House reporters and photographers have been attending church services with regularity, that has surely done them no harm.On the other hand, I realize that your staff and wire service photographers may be complaining that they do not enjoy the same green privileges at the local golf courses that they once did.

It is true that my predecessor did not object as I do to pictures of one’s golfing skill in action. But neither on the other hand did he ever bean a Secret Service man.

My topic tonight is a more sober one of concern to publishers as well as editors.

I want to talk about our common responsibilities in the face of a common danger. The events of recent weeks may have helped to illuminate that challenge for some; but the dimensions of its threat have loomed large on the horizon for many years. Whatever our hopes may be for the future–for reducing this threat or living with it–there is no escaping either the gravity or the totality of its challenge to our survival and to our security–a challenge that confronts us in unaccustomed ways in every sphere of human activity.

This deadly challenge imposes upon our society two requirements of direct concern both to the press and to the President–two requirements that may seem almost contradictory in tone, but which must be reconciled and fulfilled if we are to meet this national peril. I refer, first, to the need for a far greater public information; and, second, to the need for far greater official secrecy.

The very word "secrecy" is repugnant in a free and open society; and we are as a people inherently and historically opposed to secret societies, to secret oaths and to secret proceedings. We decided long ago that the dangers of excessive and unwarranted concealment of pertinent facts far outweighed the dangers which are cited to justify it. Even today, there is little value in opposing the threat of a closed society by imitating its arbitrary restrictions. Even today, there is little value in insuring the survival of our nation if our traditions do not survive with it. And there is very grave danger that an announced need for increased security will be seized upon by those anxious to expand its meaning to the very limits of official censorship and concealment. That I do not intend to permit to the extent that it is in my control. And no official of my Administration, whether his rank is high or low, civilian or military, should interpret my words here tonight as an excuse to censor the news, to stifle dissent, to cover up our mistakes or to withhold from the press and the public the facts they deserve to know.

But I do ask every publisher, every editor, and every newsman in the nation to reexamine his own standards, and to recognize the nature of our country’s peril. In time of war, the government and the press have customarily joined in an effort based largely on self-discipline, to prevent unauthorized disclosures to the enemy. In time of "clear and present danger," the courts have held that even the privileged rights of the First Amendment must yield to the public’s need for national security.

Today no war has been declared–and however fierce the struggle may be, it may never be declared in the traditional fashion. Our way of life is under attack. Those who make themselves our enemy are advancing around the globe. The survival of our friends is in danger. And yet no war has been declared, no borders have been crossed by marching troops, no missiles have been fired.

If the press is awaiting a declaration of war before it imposes the self-discipline of combat conditions, then I can only say that no war ever posed a greater threat to our security. If you are awaiting a finding of "clear and present danger," then I can only say that the danger has never been more clear and its presence has never been more imminent.

It requires a change in outlook, a change in tactics, a change in missions–by the government, by the people, by every businessman or labor leader, and by every newspaper. For we are opposed around the world by a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that relies primarily on covert means for expanding its sphere of influence–on infiltration instead of invasion, on subversion instead of elections, on intimidation instead of free choice, on guerrillas by night instead of armies by day. It is a system which has conscripted vast human and material resources into the building of a tightly knit, highly efficient machine that combines military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific and political operations.

Its preparations are concealed, not published. Its mistakes are buried, not headlined. Its dissenters are silenced, not praised. No expenditure is questioned, no rumor is printed, no secret is revealed. It conducts the Cold War, in short, with a war-time discipline no democracy would ever hope or wish to match. Nevertheless, every democracy recognizes the necessary restraints of national security–and the question remains whether those restraints need to be more strictly observed if we are to oppose this kind of attack as well as outright invasion.

For the facts of the matter are that this nation’s foes have openly boasted of acquiring through our newspapers information they would otherwise hire agents to acquire through theft, bribery or espionage; that details of this nation’s covert preparations to counter the enemy’s covert operations have been available to every newspaper reader, friend and foe alike; that the size, the strength, the location and the nature of our forces and weapons, and our plans and strategy for their use, have all been pinpointed in the press and other news media to a degree sufficient to satisfy any foreign power; and that, in at least in one case, the publication of details concerning a secret mechanism whereby satellites were followed required its alteration at the expense of considerable time and money.

The newspapers which printed these stories were loyal, patriotic, responsible and well-meaning. Had we been engaged in open warfare, they undoubtedly would not have published such items. But in the absence of open warfare, they recognized only the tests of journalism and not the tests of national security. And my question tonight is whether additional tests should not now be adopted.

The question is for you alone to answer. No public official should answer it for you. No governmental plan should impose its restraints against your will. But I would be failing in my duty to the nation, in considering all of the responsibilities that we now bear and all of the means at hand to meet those responsibilities, if I did not commend this problem to your attention, and urge its thoughtful consideration.

On many earlier occasions, I have said–and your newspapers have constantly said–that these are times that appeal to every citizen’s sense of sacrifice and self-discipline. They call out to every citizen to weigh his rights and comforts against his obligations to the common good. I cannot now believe that those citizens who serve in the newspaper business consider themselves exempt from that appeal.

I have no intention of establishing a new Office of War Information to govern the flow of news. I am not suggesting any new forms of censorship or any new types of security classifications. I have no easy answer to the dilemma that I have posed, and would not seek to impose it if I had one. But I am asking the members of the newspaper profession and the industry in this country to reexamine their own responsibilities, to consider the degree and the nature of the present danger, and to heed the duty of self-restraint which that danger imposes upon us all.

Every newspaper now asks itself, with respect to every story: "Is it news?" All I suggest is that you add the question: "Is it in the interest of the national security?" And I hope that every group in America–unions and businessmen and public officials at every level– will ask the same question of their endeavors, and subject their actions to the same exacting tests.

And should the press of America consider and recommend the voluntary assumption of specific new steps or machinery, I can assure you that we will cooperate whole-heartedly with those recommendations.

Perhaps there will be no recommendations. Perhaps there is no answer to the dilemma faced by a free and open society in a cold and secret war. In times of peace, any discussion of this subject, and any action that results, are both painful and without precedent. But this is a time of peace and peril which knows no precedent in history.

It is the unprecedented nature of this challenge that also gives rise to your second obligation–an obligation which I share. And that is our obligation to inform and alert the American people–to make certain that they possess all the facts that they need, and understand them as well–the perils, the prospects, the purposes of our program and the choices that we face.

No President should fear public scrutiny of his program. For from that scrutiny comes understanding; and from that understanding comes support or opposition. And both are necessary. I am not asking your newspapers to support the Administration, but I am asking your help in the tremendous task of informing and alerting the American people. For I have complete confidence in the response and dedication of our citizens whenever they are fully informed.

I not only could not stifle controversy among your readers–I welcome it. This Administration intends to be candid about its errors; for as a wise man once said: "An error does not become a mistake until you refuse to correct it". We intend to accept full responsibility for our errors; and we expect you to point them out when we miss them.

Without debate, without criticism, no Administration and no country can succeed–and no republic can survive. That is why the Athenian lawmaker Solon decreed it a crime for any citizen to shrink from controversy. And that is why our press was protected by the First Amendment– the only business in America specifically protected by the Constitution- -not primarily to amuse and entertain, not to emphasize the trivial and the sentimental, not to simply "give the public what it wants"–but to inform, to arouse, to reflect, to state our dangers and our opportunities, to indicate our crises and our choices, to lead, mold, educate and sometimes even anger public opinion.

This means greater coverage and analysis of international news–for it is no longer far away and foreign but close at hand and local. It means greater attention to improved understanding of the news as well as improved transmission. And it means, finally, that government at all levels, must meet its obligation to provide you with the fullest possible information outside the narrowest limits of national security–and we intend to do it.

It was early in the Seventeenth Century that Francis Bacon remarked on three recent inventions already transforming the world: the compass, gunpowder and the printing press. Now the links between the nations first forged by the compass have made us all citizens of the world, the hopes and threats of one becoming the hopes and threats of us all. In that one world’s efforts to live together, the evolution of gunpowder to its ultimate limit has warned mankind of the terrible consequences of failure.

And so it is to the printing press–to the recorder of man’s deeds, the keeper of his conscience, the courier of his news–that we look for strength and assistance, confident that with your help man will be what he was born to be: free and independent. born to be: free and independent. ♦